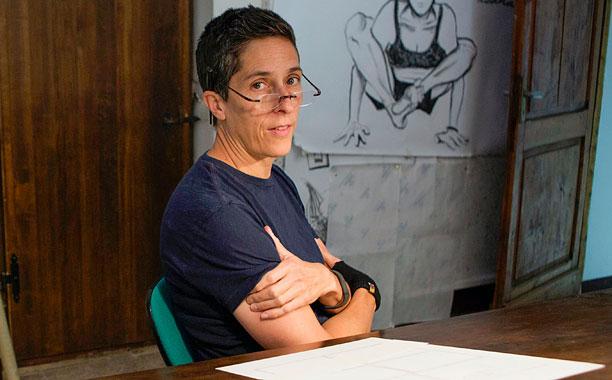

Alison Bechdel seems a bit nonplussed about her success.

The recent Tony Award-winner, also author of the long-running cartoon Dykes to Watch Out For and two graphic novel memoirs, Fun Home (2006) and Are You My Mother? (2012), has earned the kind of recognition not normally accorded cartoon- ists. This year, her book Fun Home was adapted into a musical that was nominated for 12 Tony Awards and won

five, including Best Musical, and last year she received the MacArthur “genius” grant.

“I don’t know how talented I am, but I just like to do it,” she says of her success.

Bechdel is also associated with the well-known (at least on college campuses) Bechdel Test. The test, which Bechdel says a friend, Liz Wallace, came up with, determines whether a movie is sexist by asking just three questions: 1) are there two or more female characters; 2) who speak to one another; and 3) not only about men? This seemingly simple test reveals just how widespread sexism is in the movie industry. The term grew from a one-panel cartoon Bechdel made in 1985.

The 54-year-old Vermont resident, who majored in studio art and art history at Oberlin College, doesn’t remember ever not doodling.

“I always drew, from when I was a tiny kid, like we all do,” Bechdel says. “Unlike most people who stop at some point, I just kept going.”

Bechdel also is an inveterate journal keeper. Some of her earliest memories re- volve around her journal and how she developed some obsessive behaviors center- ing on it. It grew, she says, from her search for truth with a capital “T.” She took to inserting “I think” after every statement in her journal, since she could not be absolutely certain that things happened as she thought they did. Soon, a shorthand developed, where she drew a caret over first the pronouns, then whole paragraphs and pages. Her obsessive behaviors eventually passed, but she still has her journals, which she refers to extensively in her work.

“When I was a kid I wanted to [be a cartoonist] but everyone convinced me it was an unrealistic employment goal,” says Bechdel. “I had given up on the idea.”

Both of Bechdel’s parents were English teachers and NCTE members. (She remembers her mother going to NCTE Conventions.) Bechdel’s memoirs, full of literary allusions, reflect her parents’ influence. Neither viewed the idea of her being a cartoonist with much approval.

In college Bechdel discovered she was lesbian. In many of the scenes in Fun Home she draws the stacks and stacks of feminist/lesbian-themed books she read on the side: a personal independent study.

Bechdel decided that if she couldn’t be a cartoonist, she’d be a graphic artist or book designer, but wasn’t accepted by any of the graduate programs she applied to. Moving to New York City with her girlfriend, she dove into the feminist/lesbian culture of the ‘80s, “which was very exciting,” she says. There she began Dykes to Watch Out For (DTWOF).

DTWOF started out as a single- panel cartoon—“basically a doodle with a caption.” The project was her effort to portray her world through a positive lens. The cartoon grew into a strip that was carried by 50 alternative papers for 25 years. As for choosing graphic novels and comics, in some ways this was the ultimate rejection of her parents’ “highbrow” literary tastes, she says.

“Comics were a ‘loser’ thing to do, and that was the beauty of it,” said Bechdel in a New Yorker profile. “I liked being an outsider. It gave me an objectivity that I thought I would forfeit if I was normal.”

Despite enjoying being an outsider, Bechdel has somewhat unintentionally tapped into deep feelings shared by many.

Katie Roiphe, in a 2012 New York Times Book Review article about Are You My Mother?, writes, “I haven’t encountered a book about being an artist, or about the punishing entanglements of mothers and daughters, as engaging, profound, or original as this one in a long time. In fact, the book made such a deep impression on me that after reading it, I walked around for days seeing little bits and snatches of my life as Alison Bechdel drawings.”

Bechdel came out to her parents when she was in college via letter. A few months later, her father, a closeted gay man, committed suicide by step- ping in front of a bread truck. This combination of events was the catalyst for Bechdel’s embarking on Fun Home, which took her seven years to write.

At a 2008 talk at Cornell University, Bechdel talked about how, if language is unreliable and appearances, deceiving, “maybe by triangulating between these two things, you could get a little closer to the truth.” Telling the truth has been a compulsion for her from an early age.

As for her fame, Bechdel is clearly ambivalent about it. She insists she is nothing special, one of a large group of accomplished cartoonists. She doesn’t know what makes her work different. She hesitates when praised. “I think they’ve become a little hysterical,” she says of the critics heaping acclaim on her. She will allow that her career has had “a rather surprising arc,” but asserts that comics have been growing in respectability for decades.

“The culture is recognizing that you can have good graphic novels,” she says. “That didn’t use to be the case. Cartoonists are creating much more complicated stories and the medium is in a mode of expansion and experimentation that is really amazing.”

“I feel like when my book came out it caught a wave at a time when people were really ready to acknowledge this,” she says.

She also admits that perhaps her book was “particularly literary in its context,” making it of more interest to regular book reviewers than many graphic novels.

For all their growing cachet, Bechdel says, there are good and bad graphic novels.

“You wouldn’t give a kid just any book to read,” and that holds true for graphic novels as well, she says.

In her own work, Bechdel continues to experiment with the medium.

“I am always trying to figure out how to make comics do a little more,” she says. “It’s not the con- tent, it’s the way of conveying information and telling a story, the way I can do that with access to both these registers, of writing and draw ing— that’s the exciting thing to me, not what I’m talking about so much.”

Although much of Bechdel’s work is memoir, she looks elsewhere for inspiration as well. Bechdel “doesn’t read as much as she should,” even though as a child she read constantly and indiscriminately. She loved “all those little biographies that came in a set! I just read right through them.”

Lately Bechdel has been reading a lot of biographies, including “an amazing one” by Oliver Sacks, and she just finished a biography of Margaret Fuller (1810–1850), the New York Tribune’s female foreign correspondent. (“We all have to know about this woman,” Bechdel says of Fuller. “She was totally ahead of her time.”)

One reason Bechdel loves making comics, she says, is that the act of combining words and pictures most closely approximates how humans think.

“And that’s kind of how our memories work. All these images are coexisting at once in our minds. We’re used to thinking like that, so it’s making use of the way our brains naturally work.”

In answer to what comes first for her, the words or the pictures, Bechdel says, essentially, “both.”

“I’m never able to accurately describe the interaction of those two planes,” she says. “I feel like they are somewhat simultaneous, but if you were watching me it would look like I was writing first and drawing later. But when I’m writing I’m thinking about images and those drive my narrative as much as the words do.”

And now that Bechdel has hit the big time, how does she feel about the possibility of being a role model or inspiration to young kids wrestling with their own sexual identity?

“I come from this earlier generation of gay people who are always a little nervous when talking about kids, high school kids,” she says. “We weren’t allowed to talk about gay stuff. It’s a new landscape that is very exciting, but I still have feelings of hesitation.”

Bechdel’s own coming-out process, pre-Internet and social media, was a bit more of an odyssey.

“I cobbled things together,” she says. “I’d accidentally find a little glimpse of a gay character or an unconventional character, just sort of hang on to those little glimpses.”

She remembers one book in particular, The Front Runner (1974), by Patrica Nell Warren, that was a real eye-opener. The book is a love story about two gay men who are Olympic athletes. “I discovered this when I was 14 or 15, and it was a gay love story which was completely ‘this is fine,’” says Bechdel. “It treated the characters very positively. That changed the possibilities for me.”

And how does she feel about the fact that her own work is being taught in schools more and more frequently?

“I’d sort of, in a way, prefer to be a secret, something that kids discover, not that kids get taught,” she says. “I’m a little leery of that happening. I kind of prefer to be forbidden.”

To view Bechdel’s 2008 Cornell talk, visit www.cornell.edu/video/reading-by-graphic-novelist-alison-bechdel

0 Comments